Saint-Domingue, Haiti & Charleston

The diocese’s long connection to Haiti

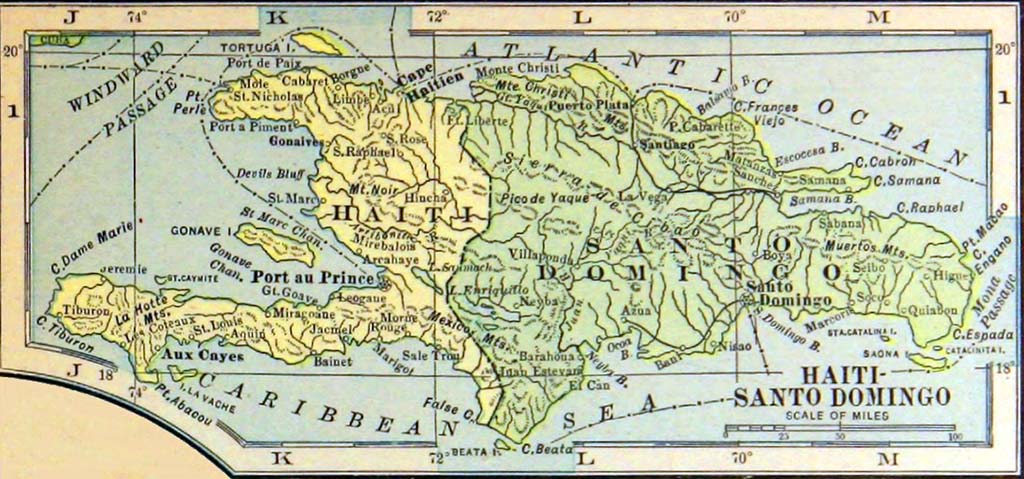

The histories of France, Saint-Domingue, Charleston, and Haiti are closely bound. Refugees escaped France (1789 – 1799) throughout the decade-long French Revolution. When the Revolution reached the island colony of Saint-Domingue, it created another stream of refugees which met their continental counterparts in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1780 Saint-Domingue was one of the wealthiest colonies in the world. It was so valuable to France that in 1697 France gave the entire colony of New France (Canada) to England to retain Saint-Domingue. The Haitian Revolution which began in 1791 eventually liberated the colony and created the Haitian Republic in 1804.

During a century of French rule planters imported an estimated 800,000 Africans to produce sugar, coffee, and cotton. While Saint-Dominguans were not generally considered devout Roman Catholics, some Whites, such as the Berard family, took their religious responsibilities seriously. When the Berards fled to New York, their slaves accompanied them. Pierre, an enslaved Catholic, supported his White owners in exile and purchased his enslaved family members before he was freed. He adopted the surname Toussaint in honor of the Haitian revolutionary leader, Toussaint Louverture. He also supported the Black women from Saint-Domingue who founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence at Baltimore, Maryland. Venerable Pierre Toussaint is now on the path to sainthood in the Catholic Church.

During its colonial era Saint-Domingue was a three-tiered society comprising Whites, mixed-race, free and enslaved Black people. It was a place where young Frenchmen could make their fortunes. When French-speaking Catholics — whites, enslaved Blacks, and free people of color — arrived in Charleston they radically changed the social and religious milieu of Protestant, two-tiered South Carolina.

Irishmen initially organized Charleston’s large, international Catholic community. The vestry appointed a manager just for French members, some of whom were members of the Brown Fellowship Society, a benevolent burial society. The earliest baptismal registers of St. Mary’s (1792 to 1821) records 884 baptisms, 600 Whites and 284 Blacks. Of the total, there were 342 French Whites, free and enslaved Blacks. Since South Carolina law forbade manumission there were few free Blacks. Black French refugees challenged Charleston’s social stability. The 1790 Federal Census listed 8,089 whites and 586 free blacks in Charleston and 7,684 enslaved people. In the 1820 Census free black Carolinians equaled 6,826 while the enslaved population numbered 258,475. To further restrict Black freedom, the General Assembly enacted a Capitation Tax on free people and the City of Charleston doubled that tax.

The ideals of religious freedom and the separation of church and state gave some Irish Catholics incentive to hire and fire their own pastors and claim full legal rights over management of the congregation preferring Irish priests. French Catholics preferred French speaking priests. In 1812 Archbishop John Carroll sent to Charleston newly ordained Fr. Joseph-Pierre Picot de Limoëlan, Chevalier de Clorivière (1768 – 1826), a Breton nobleman with an ‘interesting past’. In 1800 he was a leader of an unsuccessful Royalist plot to assassinate Napoleon Bonaparte. Limoëlan fled to America, changed his name to Clorivière, discerned a vocation to the priesthood, and was ordained at the French-led seminary in Baltimore, Maryland. The notorious assassin Limoëlan transformed himself into pious Father Clorivière. Despite the positive life change, Clorivière’s American reputation rests on the conflict with his Irish congregation known as the ‘Charleston Schism.’ In hindsight, the newly ordained Fr. Clorivière was the least likely French-speaking priest the archbishop could have chosen for Charleston. The Charleston Schism pitted republican Irish laymen who sought to adopt decentralized Protestant church structure against a French aristocratic former terrorist who upheld hierarchy in law and in Church. Father Clorivière was the Old Regime foil to a spectrum of republican ideals.

Tension between rebellious Irish and Old Regime French within the Catholic community became so heated that Archbishop Leonard Neale placed St. Mary’s under interdict in 1817. Interdict meant that Mass and all spiritual functions were forbidden, and the only Catholic Church in Charleston was closed. The controversy was resolved when Rome appointed Irish-born Father John England to be bishop of the new diocese of Charleston in 1820. Well-educated, eloquent, and outspoken in defense of Catholicism as well as republican ideals, the Irish bishop was a good choice for Charleston. In Ireland he appealed to oppressed Catholics, Protestants, and monarchists. A trustee of the Cork Mercantile Chronicle, he was also a journalist.

In the 1830s Great Britain led international efforts to abolish slavery. Most European powers followed, including Pope Gregory XVI because this goal coincided with his attempt to regularize Church relations with nations after the revolutionary era. In 1832 Rome sought to bring the Haitian church to obedience to Rome. Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer agreed to negotiations but insisted on retaining control of churches and clergy as it had been in the French revolutionary era. In 1833 Pope Gregory XVI appointed John England Apostolic Delegate to Haiti to negotiate the agreement because the Charleston diocese had a large Haitian Catholic population. The mission put England in a precarious position in South Carolina which was still shaken by the Denmark Vesey Conspiracy of 1822. Carolinians were also passionate about the Nullification Crisis. Ostensibly about national tariffs, that controversy was also about slavery. England, sensitive to Charleston political pressure, knew the Haitian mission was a serious threat to his diocese. When talks with Boyer stalled, England returned to South Carolina where he faced vocal opposition. The Catholic bishop had been in the good graces of the leading Southerners, but his work on the Papal mission was now seen as a betrayal of the South. Rumors included speculation that England would use his legatine powers to establish the Inquisition in the United States. Or he was plotting to overthrow slavery. For the four years he was involved in the Haitian affair, emotions ran so high in Charleston, that the bishop was forced to close his school for Blacks. Charleston’s powerbrokers, Robert Young Hayne, James Hamilton, Junior, and James Louis Petigru, urged him to drop the mission since it was damaging his Catholic and pro-slavery reputation.

In December 1835 England presented a routine incorporation petition to the South Carolina General Assembly. Angry legislators blocked the petition because of the ‘taint’ of the Haitian mission. In his defense England made an eloquent appeal that explained his Catholic responsibilities in detail. Alluding to recent anti-Catholic convent riots, he urged the General Assembly not to ‘degrade’ Carolina by comparing it to Massachusetts. His petition passed the Assembly, and he made one last trip to Haiti. Nevertheless, the mission eroded the bishop’s position with slaveholders and alliance with southern Protestants.

Pope Gregory’s 1839 apostolic letter coincided with rising American tensions over slavery. John England refused to believe the Pontiff threatened southern slaveholders who still suspected the bishop of abolitionist sentiments. In 1841 England addressed these issues in letters to John Forsyth, a Georgia politician, but the eloquent Irishman died before he completed the task.

By Suzanne Krebsbach, independent scholar, author, and former corporate and law librarian. She has written extensively on Catholicism and Black Catholics in South Carolina.